I was recently asked to do a small newsletter for the SIMBA project shortly describing the intervention and where we were in the process of getting it started. I thought it would be a good idea to update you as well on the project process.

We have been working hard on getting the ethical approval and on the 16th of September we got the go-ahead. We have just hired Simon, a Ph.D. student, to help out with the practical work on the project. There will be a lot to do with recruitment, running examinations and other practical parts of running a human trial.

The newsletter also contains a short description of the major hypothesis and a bit about the design of the study. Hope you enjoy the news! (continues after the picture)

SIMBA newsletter

Globally, the incidence of obesity and related metabolic diseases are steeply increasing, and this has major consequences both for individuals as well as the health care system worldwide. This urgently calls for early preventive strategies, but also for treatments targeting the early developing stages of diseases such as metabolic syndrome. The gastrointestinal system and the gut microbiome, in particular, have been proposed as a key target for such interventions. A dysbiotic, or altered, gut microbiome has been associated with increased metabolic and immune disorders in humans, affecting insulin secretion, fat accumulation, energy homeostasis and plasma cholesterol levels and initially manifests as metabolic syndrome, a health condition that places people at a higher risk of cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes and some cancers. Therefore, the gut microbiome may serve as a potential therapeutic target for metabolic syndrome. However, only a few potential candidates for alleviating metabolic syndrome via gut microbiome manipulation have been tested in humans.

This is about to change with the SIMBA project. As part of Work Package 5, a novel, sustainable, fermented plant-based dietary supplement will be tested on humans. The product, developed by our partner FermBiotics, is a fermented canola-seaweed product that is produced via a lactic acid bacteria driven fermentation of canola (rapeseed) and seaweed. The product is rich in glycosinolates and putatively prebiotic oligosaccharides, and it’s projected to have a huge impact on the human gut microbiota, and thereby human health.

The intervention study will be carried out as a double-blinded, placebo-controlled randomized controlled trial using a parallel design, with 100 obese participants consuming 5 grams/day of fermented seaweed and canola, or a rye cereal placebo. The participants will be instructed to maintain their daily routines throughout the six-week study, and thus potential changes would be mediated only by the supplement.

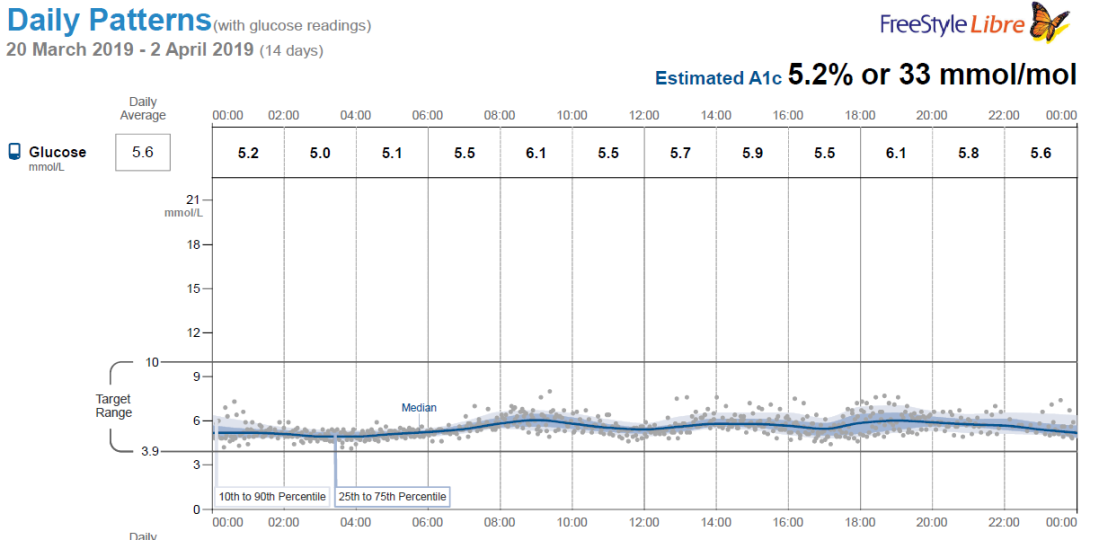

We will study the effects of the fermented canola-seaweed product on glucose handling and related cardiometabolic traits such as dyslipidemia and low-grade systemic inflammation. At each visit, an oral glucose tolerance test will be conducted to investigate insulin sensitivity by measuring 30- and 120-min blood glucose. Moreover, a small number of participants will also be included in a sub-study where they will have blood glucose levels monitored with a 24-hour continuous glucose monitoring for 14 days. We will also measure anthropometry and blood pressure. Finally, we will examine the gut microbiota and the metabolic phenotype of the subjects to explore molecular mechanisms related to the potential improvements.

Recruitment of participants has started in October 2019 and the final participants are expected to finish the trial in March 2020. The study will provide a better understanding of how a sustainable, fermented plant-based dietary supplement could be used as a potential supplement to alleviate obesity-related metabolic disorders in a population at high risk of developing type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Furthermore, the study will examine whether the product can affect obesity-related metabolic disorders through modulation of the gut microbiota and host metabolome. We expect this study to enhance our insight into useful and valuable interventions for future development of microbiota-based interventions for patients with obesity and related metabolic disorders.

I’m happy to announce that I’m working on a new project which is centered around a dietary intervention study in Greenland. The overall objective of the study is to investigate a traditional Inuit diet compared to a westernized diet in Greenland Inuit. The reason we are examining this is that the lifestyle of Inuit in Greenland is undergoing a transition from a fisher-hunter society, with a physically active lifestyle and a diet based on the food available from the natural environment, to a westernized society. Parallel to this, a rapid increase in the prevalence of lifestyle diseases such as type 2 diabetes and obesity has been observed[1]. What we are especially interested in is whether switching to a more traditional Inuit diet could improve glycemic control and thus prevent the development of type 2 diabetes.

I’m happy to announce that I’m working on a new project which is centered around a dietary intervention study in Greenland. The overall objective of the study is to investigate a traditional Inuit diet compared to a westernized diet in Greenland Inuit. The reason we are examining this is that the lifestyle of Inuit in Greenland is undergoing a transition from a fisher-hunter society, with a physically active lifestyle and a diet based on the food available from the natural environment, to a westernized society. Parallel to this, a rapid increase in the prevalence of lifestyle diseases such as type 2 diabetes and obesity has been observed[1]. What we are especially interested in is whether switching to a more traditional Inuit diet could improve glycemic control and thus prevent the development of type 2 diabetes.